|

| The

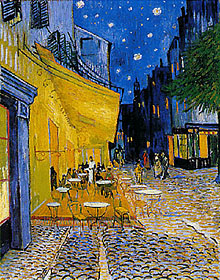

Café Terrace at Night, Vincent Van Gogh, 1888 The Café Terrace September 1888  echnique? Of all, Milliet,

how often you've watched me, echnique? Of all, Milliet,

how often you've watched me,you should know technique's worth a damn. What counts is the thing--not the subject, that's heaved with technique--the thing bare in sunlight, its colors and planes, and how the mind's furnace takes the sun's bisque to a firing hot as inside the sun. When you stand on Montmajour and stare, as you found me last spring, over the Crau, all that you've got only by knowing is lost-- the reed or the brush drags the hand by a law deeper won. Remember those figs we stole in the garden? So plumped up with sunlight and sweet? Let the eye be as loyal to light as your tongue to that taste. That painter--by his lights-- disdaining this landscape as less than the ocean. No value? No contrast? Be damned. That train, right angles crawling on steel; the fields' crazyquilt of color and shape; beyond the orchards Arles fading in mist, hung between earth and the cyan sky. All got, as I taught you, by the eye freeing the hand to know how far to push, to exaggerate color and form, retaining the facture, the play of brush stroke on canvas apart from the thing, reinforcing the thing, insisting this was seen, this was felt-- but this. partly away when I pass. While you were North, I've had exploits-- though not a soldier like you, I've started to conquer the night. To get the light--that's the trick. The deep blue and violet and citron--stars hung like globes or the globes hung like caught stars on the terrace--points of light igniting the dark; let the eye see as never in Antwerp, never in Neunen or Paris, how the darkness cups light. Can you tell from my twinkle, my friend, how I managed? Madman, they thought me before-- let them laugh. How to see the array of the palette, the way pigment falls on the canvas, without disturbing the natural light? I dragged out my easel, my box full of brushes and paints, my straw hat decked with candles--lit up like a table for two. Damn the gossip-- it worked. To get the right glow, I'd light one, then another, snuff the one out, try again. But once I'd got it, I saw clearly--clearly, you get me?--enough light for the palette and canvas, but the lamps on the terrace shone brightly, just their own light gleaming on tables, catching the eyes of the few out that late as they watched the queer devil daubing his paints and kept sipping. And the stars! The sky full, with a few down low in the wedge between rooftops, the motes in God's eye. inside, trying to render the hell of an all-night café--not a moral, the sensation, so one might know, without blearing his eyes till the rims redden from thick cords of smoke and too much absinthe, how a man could go mad from the sulphurous light--I've done the walls red, the floor the same sulphur yellow as lamps that turn faces green. Roulin loves it. Slumped figures too tired or drunk to find home--if they've got one--and one with a woman whose home is the house for those with no home. Not that I paint for the meaning-- but to paint as Flaubert uses pen strokes to capture the world, admitting no subject. What it's like is all that it means. That scene where young Emma licks out the last drop from the glass, so common, so beautifully gotten--that pink wedge of tongue-- can't you see it? Can't you feel Charles squirm as he feels the tongue working him? This one's the best since my sower last June, earth ploughed violet and orange, the sky spread yellow with highlights of green, only the brushstroke describing the boundary between sky and sun, between trousers and furrow-- light as it feels. no Ruths or Rachels--unless our Rachel; not as Venus, as Rachel herself. What a portrait she'd make--the value of light on her skin, how dark her eyes glow. That's a woman--who knows to let a man talk, like a geisha. A man alone, like us, needs more than the swamp between legs. I can do without home, but soft words, a gentle touch when it's done and a generous ear. It's the little I ask for. The rest--you've met Theo-- he'll soon find a woman, a wife, and then children. I leave it to him--I haven't time. I'm already married to paint. This summer you learned how much like a woman it pulls at your time; you chose--and wisely!--your commission over this fooling with canvas. Someday you'll settle; I wrote my sister to leave off the art, to marry a good man--a clerk or soldier. I was thinking of you. But not both--soldier and marry or marry the paint. Gauguin-- my friend who will join me, he's written--he knows. A wife and two daughters, he left them--he gives what he can, mostly love, and that such as l'Art permits-- the jealous bitch. Ah, but what he's achieved!--painted Breton wives, so moved by a sermon, they witness Jacob locked with the angel in a red field of corn. That's the way. I can see it, the canvas not licked to a burnish, the grain showing through, paint holding the texture of brush--trowelled on like mortar, like the sunflowers I've painted to brighten his walls. Blues vivid as sky, the yellows I use for the sun--a symphony to warm his room, burn out the northern cold that's laid up his hand. need a bed--not just any--and a dresser. Oh, how it will be--and now with the news that you're leaving--we will talk, we will paint side by side, such studies--new Monticellis, Delacroix's facture applied to the south, to our women, the fields tidal with wheat. Oh, and the bullfights. Last week I saw them again--I wonder how one could paint it--blood and sun, the bright capes and costumes, that sweep of the arm like broadcasting seed to display the ear--his pennant. And the flowers. I must work fast--there's much left to do. Tonight, on the Rhône, I want just the stars, those sharp points of light to suggest where the soul journeys after the body has left it. to live without God--without a wife and a child--but I need something greater. In my sower, in Gauguin's Breton wives envisioning Biblical passion--the stroke, the radiant color instead of a halo, evokes the sanctity that lies--spread to the eye-- behind or beyond the flat surface. Cypresses in the midday sun burn a black flame. We two, we will stroll arm in arm, Aaron and Moses, where each leaf's tongue shimmers bright praise. In the slight chill of morning, like Ruth, we'll glean the harvest, September mist wreathing the rustling ears or clutched to rocks and heather, Montmajour a Japanese print of vague distance. It will be fine.

|