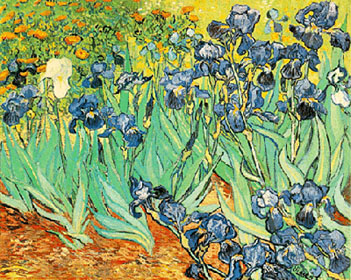

Irises, Vincent Van Gogh, 1889 In the Studio at Saint-Paul-de-Mausole June 1889  unch already? How quickly

the morning passes unch already? How quickly

the morning passeshere in the sunlight, how calmly with the pine needles swaying, almost as if to music one might, if he strained enough, hear despite the panes, a breeze I almost feel when I lose myself to the light playing on the motes swirling in the current from a forgotten wave of my arm reaching for a brush or fresh tube of paint. After lunch I'll sketch out there, I think. The heat should keep most of my fellows inside. They mean no harm, I understand, still it unnerves me to find them watching, silently, as though I were some beast behind invisible bars. No, for they have the wrong look on their faces--more as if I were performing some sacred act, the pastor revealed changing the wine to blood, the wafer become on the canvas Christ's flesh--or perhaps even Christ at Cana making the water wine, they stand so transfixed at the way the world alters shape with each stroke, almost beyond their belief how the irises there, swaying in breeze, delicately the stalks lifting free of earth to praise God with the silent tongues of their falls, come clearer in paint. Yet they spook me, they remind me too much of what I've for years feared for myself-- madness, the unplumbed depth of my soul opened like the fiery pit beneath me. So many painters wrenched by poverty to infirmity, and madness already in my family. Ah, Trabuc, how little it matters that Dr. Peyron can name my ailment-- what's a name? Call it epilepsy, as he does, and what's gained? How does that ease the fear it will again cloud my brain like a two-day debauch of absinthe, the voices calling that will not go away, not when I bury my head under pillows, not when I pray loudly to God, and when the whole world tumbles like clouds in a mistral, how could anyone not cut off an ear or plunge himself deep in a cunt and try to forget? soberly through life. And here, I eat well at least, thanks largely, Trabuc, to you, how you see to my needs. Too long I'm ill-cared for, lacking anyone to make me take time from my painting to eat. Once it's on me, it's hard to lay brushes aside. Laugh though you might, I've painted through winds threatening to blow the canvas right off the easel. Stop to eat, ha. And the difference it's made. I've never felt fitter. Look, not a tremor when I hold my hand straight out at arm's length. Christ himself could have enacted no miracle more than three meals a day. Theo worries I'll strain myself overmuch painting; in truth, it invigorates me, it helps clear my mind wrought too much perhaps by the strong light of the Midi. Was I wrong to pursue such intensity? Looking over the paintings I ship back to Paris, I can't fault the impulse, whatever the execution lacks in finesse--technique, damn it, you learn as you go, correcting the flaws as later you find them. The light, though, that light was all. Too much of a thing wears the nerves thin. That canvas takes your eye, eh? It's a new one, done not the way I like to work but sur le motif . See, there beneath the sky, the ridge of the Alpilles I see from my room, but the tree, that cypress like flame, that's from the far end of the wheat field-- here, see the start I've made of cypresses in daylight, a dark green verging on black--a hard note to hit--that scythe of a crescent moon there in the corner. And the village, where hereabouts have you seen that spire? Not Saint-Martin, surely, those low cottages wedged between the blue peaks and the edge of the canvas-- huddled by the low hearths inside the same peasants that crowd the table in my earliest efforts, dull-faced and dour-- a memory of the North. And here, in this one, see the same craggy prospect, the Alpilles, what else, but the olive orchard, those spry, tortured trees riding the spume of grass--the whole earth gone liquid, and the clouds blown in from beyond the uppermost edge of the canvas, like God's breath heaved into Adam, how it sets the world churning. How wrongly we think air without substance. Go on some warm night and watch the pliant waves, the moon and stars spinning, the currents in ether all too apparent. Nothing in the whole world is still--not just shimmering light but God's breath blown once keeps it all moving like dust in a room long after everyone's left, those cypresses dark flames, cold fire like Pentecostal tongues on the apostles' brows-- that's what the stroke captures. The eye follows the swirling brushstroke down and around, there's no place to rest, but you stand suspended between the sky and the village nestled down in the hollow. The cypress's base invisible, the closest houses cut off by the canvas's bottom. And that turbulent light! Clustered below, the small lights peering out through shuttered windows, all that human life so frail in the face of eternity, how my heart opens to each of them, stirring the last embers in the hearth, ignorant of the splendor eddying around them, before they roll themselves onto hard cots and sleep. It's that love of nature does us in. Christ, some days I sense such a terrible beauty just beyond the lucidity of paint. you'll let me paint you? I like the lines of your face, so like a hawk's, calm as you hover over each canvas, your quick eyes catching each detail as I note it, and catching clearly each tic on my face as I talk. Your lips thin--lips are the hardest to model, how patiently I've worked to get them just right in the best of my portraits. Yours almost lost beneath the mustache--but your eyes, they're the hardest. The way they soften, seeing me not as my neighbors saw me, as crazy, as dangerous. Not as one of my fellows. That poor soul who chants the day long "My mistress! My mistress!" I know too well how he suffers, but these days I feel much more rooted, even lacking all that I wanted most out of life--soon, Dr. Peyron has promised, I can return to Arles, in your care I venture, to fetch a canvas or two and the furniture left there. Perhaps you'll allow me a visit to old friends--one dear friend, Rachel. before we leave, look. I mentioned the angle. Who stands on that hillside to watch while the world tends its small business, who minds the dance, the whirlwind of light igniting his eyes? See, some of the huts are darkened already, the wicks trimmed and fire dampened. They rest.

|