|

| Woman

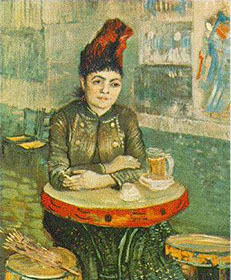

at a table in the Café du Tambourin, Vincent Van Gogh, 1890 Le Tambourin 19 May 1890  lives, I told them, and

I must be acting calm enough, they let me lives, I told them, and

I must be acting calm enough, they let meout on my own. My new little sister--Theo's married, you know, they've had their first child and named it, much as I cautioned against it--why burden the child with a name so tied to madness and pain?--for me. I could tell she was shocked from her first sight of me, rough-looking peasant that I am, the South burned in my face from the long hours of sun. Better than Theo-- pale and shaken as though it were he not his wife who'd suffered confinement. Paris does that, one spends all his days in close rooms, the sun a ghost through the grating, yet all he need do is take time to stroll the boulevards, the arcades of chestnuts in bloom. I couldn't bear to live here again. Already the place wears, the talk, good as it is, even with Theo, for I doubt this trip I'll have time to meet with Pissaro, Lautrec, the old crew whose paintings you let grace your walls--but no sales, how that stung-- but I've sold one, a canvas from Arles, to a woman in Brussels, a paltry sum given the much I owe Theo. An odd one she's taken, done when Gauguin was living in Arles and too much in debt to his style I think now--women stooping to gather grapes from vines turned crimson in the low autumn sun. color, you could not believe it, so much fruit. The peaches in bloom in the springtime, the dazzling fields blown with poppies, those irises, the blue of God's eye--why else call them iris?--and the wide groves of olives, their sinuous trunks twining the air like dancers whose feet remain rooted in earth. So human, gnarled but graceful, bent like peasants to the task--so much like a woman, you'd see it at once-- that plump orbit of hips, the delicate breasts turned upward and browned by the sun, teak, mahogany, tones you must mix for no one tube could contain them. Their branches arms spun over their heads, their faces concealed by the leaves' constant green through the summer. You walk through the orchards and the fruit near falls in your hand, so abundant--so lush, like Eden before our transgression. in my roaming for olives, green ones and black, I must have them, I swore. To suit me, they let me go out on my own. Hale as I seem, they're aware of my illness--the one thing they don't speak of, at least in my presence; instead, they avoid contention. Yesterday, after we went to Tanguy's--he'd stacked our paintings, mine and Gauguin's, and a few by Guillaumin and Bernard, and the Australian Russell, in a garret damp as the sewers-- yes, I was fuming, and Theo, too much aware of my temper--you recall those days at Rue Lepic, that cramped flat, the flare-ups-- he tried hard to trim me like a paraffin lamp turned too high. How glad I am to have found you. This much before noon, I wasn't sure where you'd be. I wasn't sure, I didn't mention your name, whether you'd even be here. How we've grown, me wizened like grapes left too long in the sun, and you--is it only three springs I've spent in the South?--my dear, how they've quenched you. Who could guess, though we lacked youth's excuse, how much life would tear. I leave it to Theo, all I desired. No--I don't blame you, nor the other--how could I dream myself a father, wreck I've become, even then, by the doctors' accounting, I carried the seed in my brain. Why, after our fall, damn a child with more of a burden than thistles and sweat? it all moves for moving so quickly. I know you grow impatient when I speak of such things, but please listen. What is there beyond what we see? The other day riding the coach from Tarascon I thought of the stars, on cold nights such sharp little glimmers, hard as the dots on a map--spread over the sky, in fact, like a map of the future. Someday my soul may sail star to star the way my frame bounced over the rails; think of it that way, and cancer, consumption, this malady gripping my skull--heavenly tickets! Why else should those far lights move me so, swim through my brain like those filaments that worm over the retina, what other than something beyond--call it God--could model olives in such graceful forms? How else could I live a lifetime in three meager springs? Theo's money runs short. A wife and a child, how long can I last? He dares not phrase it that way, even deep in his secretest thoughts, but it crosses his mind, a shadow, like you see cloud the eyes of a dog or a cat--a feeling beyond or not yet resolved into words. I long to take up his hand, press it hard to my heart and assure him: not long. He's given so much for so long. How I hate him. I can't believe that slipped into words, but it's true. All that I wanted--his. And me with this flame embering deep in the ash of my brain, he's the wan one, the weakling. No--forget what I said. God help me, some days my tongue has a mind of its own, or my hand. Last month I was barely restrained from downing a jar of thinner come to hand-- I never gave it a thought. And once--I can't even recall though they've told me--I kicked an attendant. I, who refused to kill the death's-head moth last spring, painting it as I loathed to, from memory, when its beautiful colors would not fade out of mind--that taint of carmine and olive. Mornings, after wrestling long nights with the glass, I've felt the razor shake in my fist as though on its own and tossed it away with all my resolve--it's like that, surely you've known it, only I have no control, not even awareness enough to know what I'm doing or have done. who should I turn to but God? I've seen a small sampling of Hell--those forlorn souls watching my colors render the canvas light, trudging like the prisoners in Doré's woodcut I copied in oil. What they've locked in their minds, and how their minds lock them in. Their arms hung flat at their sides, flaccid like wheat gone too long past the harvest. By the end, I couldn't stir from my rooms. I'd creep down the hall from bedroom to studio only those times I was sure I'd meet no one. They spun pain from their eyes like a spider its web. Better I sit in my room and sketch poppies in the meadow, the Alpilles tumbling over the wall beyond, and the small wedge of sky--as though no bars crisscrossed the view. Like those Japanese I read of, or Whitman recalling scenes from his mother's youth--an act of pure will. the shirt off my back--and did. How much like those wretches in the Borinage those inmates--the same tortured vacancy in their stares, the same fascination with the most insignificant thing--an osier's catkin, cicada shell clung to a grassblade, feather blown into a cuff. I've seen that look deep in the eyes of a cow the first time she calved. So unlike those cannibals at Arles, their petition, shopkeepers and tradesmen, demanding the madman be confined. Souls? The little they gained in the trade. Like those who reviled the apostles, their tongues licked pure by the glimmering tongues on their brows-- that hard Southern light. the arcades more crowded, factories befouling the air, the fields more than a walk from the center of town. Still, I've set my heart one day to paint a bookstore in Paris by gaslight-- that seed time of knowledge, the harvest of print so apt between wheatfield and olives. those dark flames in the pale fields of wheat; such color, the English, starved by clouds for sunlight--I've lived there, I know them--they'll buy them. Open that market, and all we've dreamed will happen. We have none of us seen clearly, dabble though we have at the light-- Chavannes perhaps come the closest, those he's done in the past few years, a presentiment of what lies ahead, like Gilead Moses glimpsed only from Pisgah--I'll never cross in, but there, in his olives, I've seen it. And mine, my blood fouled by the sun, if I'm lucky the few best may have watered the stone. What honey, what balm? I've seen clouds slouch like God's buttocks through a sky my brain has bleached blue. What's clouded my eyes? These minutes, the few words--I'll ship you a canvas I've done of some roses. They will last as the picked ones will not, by the end of an hour they droop on their stems, the prick gone out of the thorn. There, over the zinc bar you can hang it, a bit of light for blurred eyes to graze. Now I must fetch those olives. A handshake to any who ask.

|