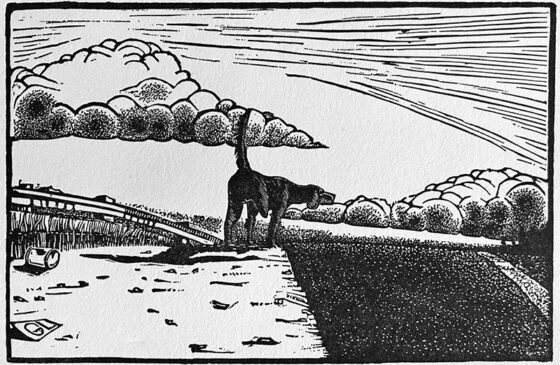

Each year, a few weeks after school let out, we would overpack one of a succession of enormous station wagons and drive a thousand miles west to Indiana. Hobson relations were liberally salted across the state, and we would manage to see most of them while doing the rounds. Corydon, Freelandville, South Bend, Indianapolis, Vincennes. From the decades of distance, they meld together–Indiana, where it was always July.

July in Indiana

It’s 85 degrees at midnight. I lean

out the window seeking a breeze.

Peepers sing to the dark, to the corn,

and the blacktop, and the rising moon.

In town a dog is barking at nothing.

Farther off a hundred freight cars

racket the rails, the engine blaring

through each deserted crossing.

I find my Dad here in this pile

pranking around with his brothers.

In the curled photos he’s dashing

and spruce in Army Air Corps khaki.

And there’s Mom, war bride-to-be,

reclining as Odalisque, adorning

a field of alfalfa, with a shy smile

for the man behind the camera.

Here’s my brother being bathed

in the sink of a 12-foot trailer–

what married students lived in

in Bloomington on the G.I. Bill.

Skip ahead and there’s sister

in a cowgirl dress and there’s

me, sporting droopy shorts

and a look of toddler anxiety.

Then three generations: grandma

and grandpa, seated, backed by

a wall of sons and daughters-in-law.

A moat of grandkids surrounding.

An odd lot of memory remains

of those summers, a few weeks

each year of Midwest swelter.

They blur together now into one:

Bare feet burning on blacktop,

swimming, drive-in movies, endless

fried chicken, corn smothered

in butter, homemade ice cream.

Every evening, thunderstorms

boiled up out of the west. We’d

rock back and forth on the porch

as the wind turned damp and cool.

That America was easy to love.

A thousand miles west of my life,

it could have been another world.

But I had to run away into the Sixties.

After, I rarely returned to Indiana.

Once to take Dad to his 50th reunion

just before he died, once to take our

daughter to great-grandma’s 90th.

But on a sweltering night I will find

myself back there, when trees flash

vivid, lightning-lit, and the heat

yields ten degrees in five minutes.

I’m back there when the night train

wails for mile after mile. We meet

again in mind, quick and dead alike,

and the long years since come undone.